2014-15

September 3, 2014 3:30 pm

September 3, 2014 3:30 pm

April 30, 2015 3:00 pm sold

April 30, 2015 3:00 pm sold

May 1, 2015 3:30 pm sold

May 1, 2015 3:30 pm sold

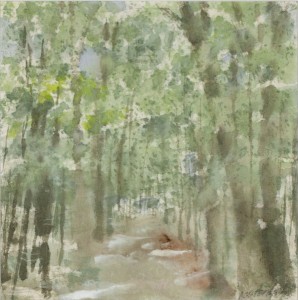

Artist Statement for In Homer Watson’s Footsteps – Homer Watson House & Gallery, 2015

This project is an attempt to follow in Homer Watson’s steps, and locate the sites from which he made his many paintings of landscapes around Doon. In my research I collected images of successive seasons in the woods near the house in which Homer Watson was born, just down the road from the Homer Watson House & Gallery; the marsh area where the Speed River and the Grand River meet; and down the Grand River into Cambridge and Paris. Homer Watson could walk from field to field across private property looking for painting subjects. He painted woods, trails, farm buildings, cows, streams and rivers.

I found images like his – riverside views, trails in the woods, individual trees, stands of trees. The paintings I made were done on the spot, following Watson’s method of “plein air” painting, a method that he himself borrowed from the painters he admired, precursors of the Impressionist movement such as Constable, Corot, and the painters of the Barbizon School (to whom he paid such affectionate homage in the ceiling frieze of his studio). Yet unlike them I used watercolour and gouache in my explorations, looking to record the fleeting light, clouds and movement in the spontaneous gestures of a fluid and quick drying medium.

Following in Homer Watson’s steps encouraged my love of old trees and showed me their cramped and dwindling environment. Gone are the huge old-growth trees of his time. What we now have, especially in Cressman Woods, are trees that were seedlings in Homer Watson’s lifetime. New private property signs multiply with the urban sprawl – no trespassing – emphatic frontiers limiting public access to woods, trail and river. I documented what I found, but I did not include new buildings or commercial developments.

Homer Watson saw the beginning of the city’s assault on the countryside and the natural environment, and the danger urban encroachment posed to the groves of old trees. His concern for his local landscape went beyond painting: it took him 25 years of work and lobbying to garner support from municipal councillors and business people to establishing Cressman Woods as a publicly accessible nature reserve, now part of Homer Watson Park.

Like Homer Watson, I want my paintings to raise our awareness that we all need these natural wooded areas, these landscapes and these points of view to be preserved for our collective health and spiritual wellbeing.

Robert Achtemichuk

Spring, 2015